Posts in Category: Collection Spotlight

Birth of a 24-Sheet

Year of Jane Russell: Day 38

Two of Hurrell’s sessions with Jane were documented in publications. The first time the pair worked together was covered in US Camera, was focused on Hurrell and his craft. The color haystack session was captured and published in the July 1942 issue of Screen Guide, an oversized publication who centered their coverage more on Jane.

Since the color haystack photos were going to be used for large format advertising, Russell Birwell’s office had pitched the Hurrell session to various magazines as the “Birth of a 24-sheet.” Screen Guide didn’t completely embrace this concept, but does mention it and included a mock-up of the envisioned billboard.

Jane, Hurrell, Esquire, and the Pioneer Safety Device Corp.

Year of Jane Russell: Day 37

The Hurrell haystack photos of Jane were alluring enough that one of them was used as a foldout in the June 1942 issue of Esquire. The staying power of these images was evident early on with the reuse of the Esquire exposure on this handout the following year for the Pioneer Safety Device Corp. Their use of the term “hay” to advertise their services is a stretch, but if nothing else, Jane certainly makes it eye catching! Of note is the credit to both Esquire and 20th Century-Fox who initially were going to distribute The Outlaw, but dropped out as the release of the film dragged out and the censorship issues intensified.

For being almost eighty years old, this handout, printed on a thick card stock has held up quite well. While the Pioneer Safety Device Corp seems to be long gone, the fetching Transportation Building located at 7th and Los Angeles streets in downtown L.A. is still alive and well!

A Little More Color

Year of Jane Russell: Day 36

The color images of a gun-wielding Jane posed on hay, taken by George Hurrell, proved popular and kept her on the cover of magazines for months, as demonstrated with this November 1942 issue of See magazine.

Jane in Glorious Kodachrome

Year of Jane Russell: Day 35

George Hurrell did a third sitting with Jane, this time in color. The images, which the publicity team referred to as “the Kodachrome photos” were expected to be used in the large scale billboards for The Outlaw. Some were also sent out to magazines who were more than happy to use them. Here’s the June 1942 issue of SPOT with one of the color Hurrells of Jane on the cover.

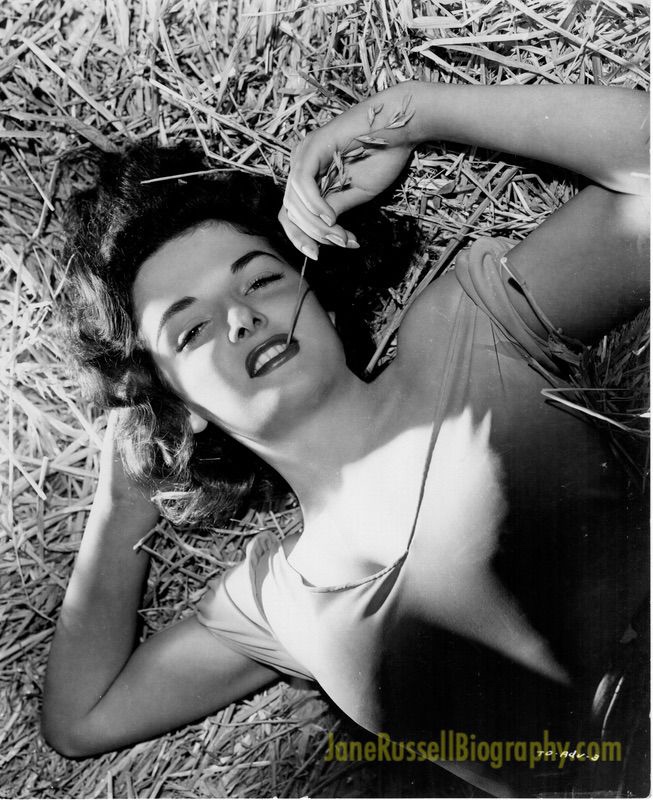

Light, Not Shadow

Year of Jane Russell: Day 34

For the haystack session, Hurrell abandoned his trademark use of light with shadow. Still, many of the photos with Jane glaring at the camera maintained the drama usually found in the photographer’s work. During the shoot, he also allowed the 20-year-old Valley Girl behind the movie make-up to reveal herself, like in this portrait.

In the Hay

Year of Jane Russell: Day 33

The second time George Hurrell photographed Jane Russell, he really embraced the theme of The Outlaw. Inspired by Jane’s first scene where she wrestles in hay with Jack Buetel, Hurrell had Jane dress up as her character Rio. He also ordered bales of hay brought into his studio which he had Jane pose on. The resulting images would become the most well known of Jane’s career.

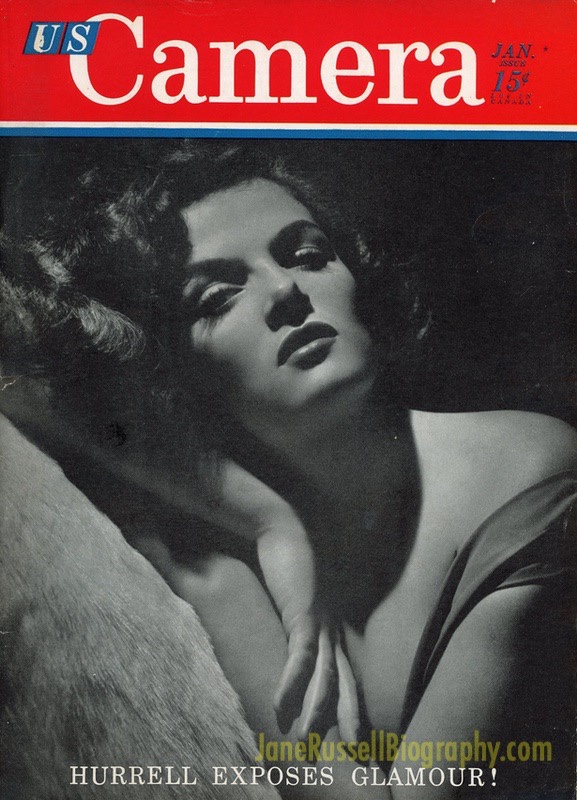

Hurrell, Jane Russell, and The Outlaw

Year of Jane Russell: Day 32

Once production on The Outlaw wrapped, Jane’s full time job became posing for photographers, who produced thousands of publicity shots that landed in newspapers and on the covers of magazines around the world. It was inevitable that publicist Russell Birdwell would send Jane to George Hurrell.

Hurrell, now considered the grandfather of Hollywood glamour photography, was a master at his craft. His use of light and shadow was extraordinary and many have tried to replicate his style. He photographed pretty much all of the big stars of the day and was well established by the time Jane showed up at his studio. Both were no-nonsense types and got along great.

Hurrell photographed Jane on at least three different occasions for The Outlaw. The first time, was a very typical Hurrell glamour shoot which was covered in the January 1942 issue of US Camera. Not only did they have a behind the scenes pictorial of Hurrell and Jane during the shoot, but they put her on the cover.

Jane, Jane Everywhere

Year of Jane Russell: Day 31

The Howard Hughes/Russell Birdwell publicity machine hit the ground running in 1941, and for Jane didn’t let up for over a decade. The effectiveness of the campaign for The Outlaw is evident with this March 1941 issue of the short-lived Friday, a far-left progressive magazine that appears to have only been published from 1940-1941. Interesting side note, the photo of Jane used on the cover was taken by Tom Kelley and was the one Levis Green spotted in the photographer’s studio which the agent showed to Howard Hawks and Howard Hughes.

On a personal note, when my grandpa passed away in 1991, we were cleaning out his garage and found his membership card to the Communist Party, a copy of The Communist Manifesto and a stack of issues of Friday. I don’t think his membership in the party lasted long, but it was some amazing insight into his young life that I didn’t know about.

International Press

Year of Jane Russell: Day 30

Russell Birdwell was the publicist mastermind behind the media campaign for The Outlaw, and was very good at his job. Even though the film would not be released (on a limited basis) until 1946, he managed to keep Jane’s name and frame out there for the entire time. The early success of the marketing of Jane Russell is evident with this French Canadian publication who put Jane on the cover before the film was complete.

Remote Communication

Year of Jane Russell: Day 29

The Arizona location shoot on The Outlaw was so remote, that cast and crew had to live in platform tents, and on the weekend would treat themselves to excursions into Flagstaff. Much ado was made about the radio telephone that was used to connect with the outside world. Here’s Jane calling her mom via radio.